The Shadow Pandemic: How COVID-19 Fueled Corruption and Ignited a Global Fightback

The COVID-19 pandemic was not only a global health crisis but also an insidious “shadow pandemic” of corruption that threatened societies, undermined democracy, and diverted essential resources. As nations scrambled to respond, the urgent need for medical supplies, economic relief, and public services created unprecedented opportunities for illicit gain. In this environment, the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC)—the central, globally accepted framework for combating this threat—became more critical than ever. This article explores the specific corruption challenges exacerbated by the pandemic and the international initiatives that emerged to fight back, reinforcing global commitments to transparency and accountability.

- The Perfect Storm: Why the Pandemic Became a Breeding Ground for Corruption

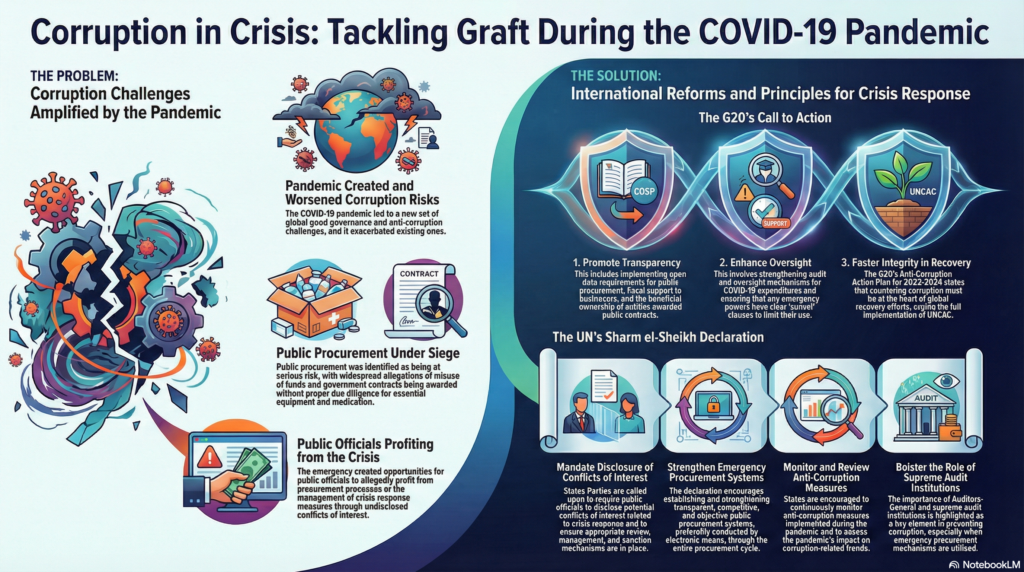

The COVID-19 pandemic created a unique and potent combination of factors that significantly increased opportunities for corruption. The urgency of the crisis, the massive scale of public spending, and the suspension of normal oversight procedures formed a perfect storm, allowing the virus of corruption to find fertile ground in weakened governance systems.

A New Set of Challenges

The pandemic led to a new set of global good governance and anti-corruption challenges while exacerbating existing ones. The rapid mobilization of resources for healthcare and economic recovery placed immense pressure on public systems, particularly procurement. The United Nations General Assembly’s 2021 Political Declaration explicitly recognized this risk, stating that “public procurement is at serious risk of corruption, including in relation to our efforts to respond to and recover from the COVID-19 pandemic“.

Key Vulnerabilities Exposed

The crisis exposed critical vulnerabilities in public systems, which manifested in several distinct ways:

- Emergency Procurement: Public officials allegedly profited from procurement processes for essential items like medical equipment and medication. The urgent need for these goods was used to bypass standard competitive bidding and transparency protocols.

- Lax Due Diligence: In the rush to secure supplies and services, government contracts were often awarded without proper due diligence checks on vendors and contractors, opening the door for unqualified or fraudulent entities.

- Conflicts of Interest: The crisis presented a particular challenge where public officials could allegedly use their status or insider knowledge to profit from the crisis response. The Conference of the States Parties to the UNCAC highlighted the need to prevent officials from leveraging their positions for personal gain in the design and management of recovery measures.

- Misuse of Funds: The massive influx of aid from international donors and development agencies created significant “leakages” in the public sector. Concerns mounted over the misuse of funds intended for the pandemic response, diverting them from their life-saving purposes.

The scale of these vulnerabilities, however, did not go unnoticed, prompting a swift and coordinated global response.

.

- A Global Awakening: How the World Responded

The surge in corruption during the pandemic triggered a global awakening and a concerted international response. Building on the foundational principles of the UNCAC, key international bodies mobilized to develop antivirals of accountability and transparency, reinforcing anti-corruption defenses to ensure that recovery efforts were both effective and accountable.

The G20’s Call to Action

The G20 issued a “Call to Action on Corruption and COVID-19,” outlining three core commitments to guide member states through the crisis and recovery:

- Promote Transparency: This focus on transparency was a direct response to the opaque nature of emergency deals, recognizing that secrecy is the oxygen that fuels corruption. By demanding open data on procurement and beneficial ownership, the G20 aimed to cut off that supply. Crucially, this commitment targets the publication of data related to public procurement, extraordinary fiscal support, and the beneficial ownership of entities awarded contracts.

- Maintain Sound Governance and Enhance Oversight: This commitment targets the need to strengthen audit and oversight mechanisms for all COVID-19 expenditures. It also commits states to limit the use of emergency powers with clear ‘sunset’ clauses (legal provisions designed to ensure that extraordinary authority granted during a crisis is temporary and subject to expiration), ensuring a return to normal governance procedures as soon as possible and preventing the crisis from becoming a pretext for unchecked authority.

- Foster Integrity in the Longer-Term Recovery: This commitment reaffirms the need to fully implement the UNCAC and use its provisions to strengthen existing checks and balances. As stated in the G20 Anti-Corruption Action Plan 2022-2024, “Countering corruption should be at the heart of our global recovery efforts“.

The United Nations’ Unified Front

The United Nations led a unified response, primarily through the Conference of the States Parties to the UNCAC (CoSP). In its 2021 political declaration, the UN General Assembly recognized corruption as a major “impediment to the achievement of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development“.

This high-level commitment was operationalized through the Sharm el-Sheikh Declaration (CoSP Resolution 9/1), the key output of the 9th Conference of the States Parties. The declaration calls upon States to take specific actions to safeguard crisis response and recovery efforts, urging member states to:

- Require public officials to disclose potential conflicts of interest to prevent them from profiting from crisis response measures.

- Ensure effective reporting systems are in place, particularly those related to the “allocation, distribution, use and management of emergency relief”.

- Strengthening the Defenses: Critical Tools in the Fight Against Corruption

The global responses to pandemic-related corruption aim to reinforce critical anti-corruption mechanisms and principles grounded in the UNCAC framework. Each tool serves as a direct antidote to the vulnerabilities the crisis so brutally exposed.

Transparent Public Procurement and Finance (Article 9)

To counter the rampant corruption seen in emergency procurement, the international response has centered on reinforcing the foundational principles of UNCAC Article 9. This article mandates that public procurement systems be based on transparency, competition, and objective criteria in decision-making. The pandemic starkly highlighted existing gaps where many states had failed to adopt specific rules on accountability and conflicts of interest for personnel responsible for procurement. Strengthening these systems is the primary defense against the diversion of funds in a crisis.

Managing Conflicts of Interest and Upholding Integrity (Articles 7 & 8)

In direct response to public officials profiting from the crisis, global initiatives have re-emphasized UNCAC Articles 7 and 8. A conflict of interest arises from a situation where a public official has a private interest that could “influence or appear to influence the impartial and objective performance of his or her official duties.” As anti-corruption analysis makes clear, a conflict of interest is not, in itself, a corrupt practice. However, it can be an indicator or precursor of corruption or, at the very least, a demonstration of a lack of integrity on the part of a public official. The UNCAC framework therefore calls for robust systems to prevent such conflicts (Article 7) and for codes of conduct to promote integrity, honesty, and responsibility among public officials (Article 8).

The Crucial Role of Supreme Audit Institutions

The misuse of public and donor funds during the pandemic underscored the indispensable role of Supreme Audit Institutions, or Auditors-General. Often referred to as the “ally of the people” and “people’s watchdogs,” their constitutional mandate is to ensure integrity and accountability in the use of public funds. This is not a mere technical function; these institutions are part of a scheme that is designed to ensure that the good governance values… enshrined in the Constitution apply to the daily administration of the country.

Their work “inherently entails the investigation of sensitive and potentially embarrassing affairs of government,” which is precisely why their independence is vital during a crisis when powerful actors may be involved. The Zambian “Zamtrop account” case provides a stark warning: when the Auditor-General failed to exercise his duties—likely due to intimidation—the president and his associates were able to loot vast sums of state money under the guise of national security, a devastating failure of a nation’s ultimate financial safeguard.

Protecting Those Who Report Corruption (Article 33)

Individuals who report corruption, often called “whistleblowers” or “reporting persons” play a vital role in exposing wrongdoing that would otherwise remain hidden. In recognition of this, UNCAC Article 33 calls for member states to consider incorporating measures to provide protection against any unjustified treatment for any person who reports corruption-related offenses in good faith. Effective protection encourages people to come forward without fear of retaliation, making them a powerful force for accountability. However, this remains a critical implementation gap. Despite the principle’s importance, many country reviews under the UNCAC Implementation Review Mechanism still recommend “the adoption of appropriate legislation and measures for the protection of reported persons” demonstrating that this is a persistent global weakness that the pandemic made all the more dangerous.

The COVID-19 pandemic did not create corruption; it brutally exposed pre-existing governance frailties that the virus of corruption was perfectly adapted to exploit. This shadow pandemic revealed the high cost of weak oversight, opaque procurement, and unmanaged conflicts of interest.

Yet, out of this crisis came a powerful and unified international commitment to fight back. The initiatives launched by the G20 and the United Nations Conference of the States Parties to the UNCAC have established a clear path forward, providing a “global blueprint for ensuring effective safeguards on national action when addressing future emergency situations“. This fightback is not merely about post-COVID recovery; it is about building systemic resilience and societal immunity for any future shock, be it another pandemic, a climate disaster, or a geopolitical crisis. By embedding the principles of the UNCAC into the very fabric of crisis response, the global community can build a foundation for the transparency, accountability, and resilience needed to face the challenges of tomorrow.

If you found this post interesting, perhaps you would like to check these:

- 5 Shocking Truths About the Money Draining the Developing World

- 5 Uncomfortable Truths About Corruption That Will Change Everything

- ESG in Latin America 2025: Real Change or Just Rhetoric?

- Regional Anti-Corruption Compliance Takes Center Stage in Latin America

- Internal Investigations: A Guide to Mitigating Corporate Risks and Ensuring Compliance

- Navigating Cartel and FTO Designations: Advanced Compliance Strategies for Global Businesses

- Mexico’s Corruption Crisis Deepens: 2024 CPI Reveals Historic Low & Global Implications

- FCPA Enforcement Pause: 5 Critical Compliance Strategies to Mitigate Risk Now

- The Essential Guide to KYC Regulations in Mexico: What Real Estate Professionals, Financial Institutions, and Buyers Must Know